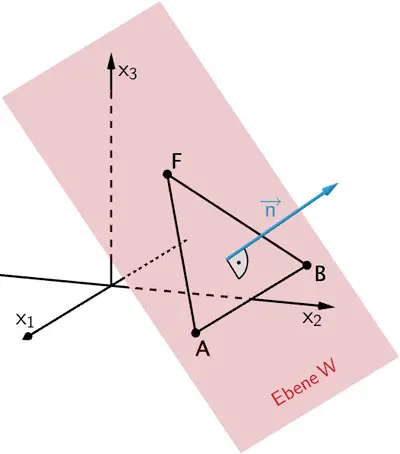

Das Dreieck \(ABF\) liegt in der Ebene \(W\). Ermitteln Sie eine Gleichung von \(W\) in Koordinatenform und beschreiben Sie die besondere Lage von \(W\) im Koordinatensystem.

(zur Kontrolle: \(W \colon 4x_{2} + 3x_{3} - 20 = 0\))

(4 BE)

Lösung zu Teilaufgabe b

Gleichung von \(W\) in Koordinatenform

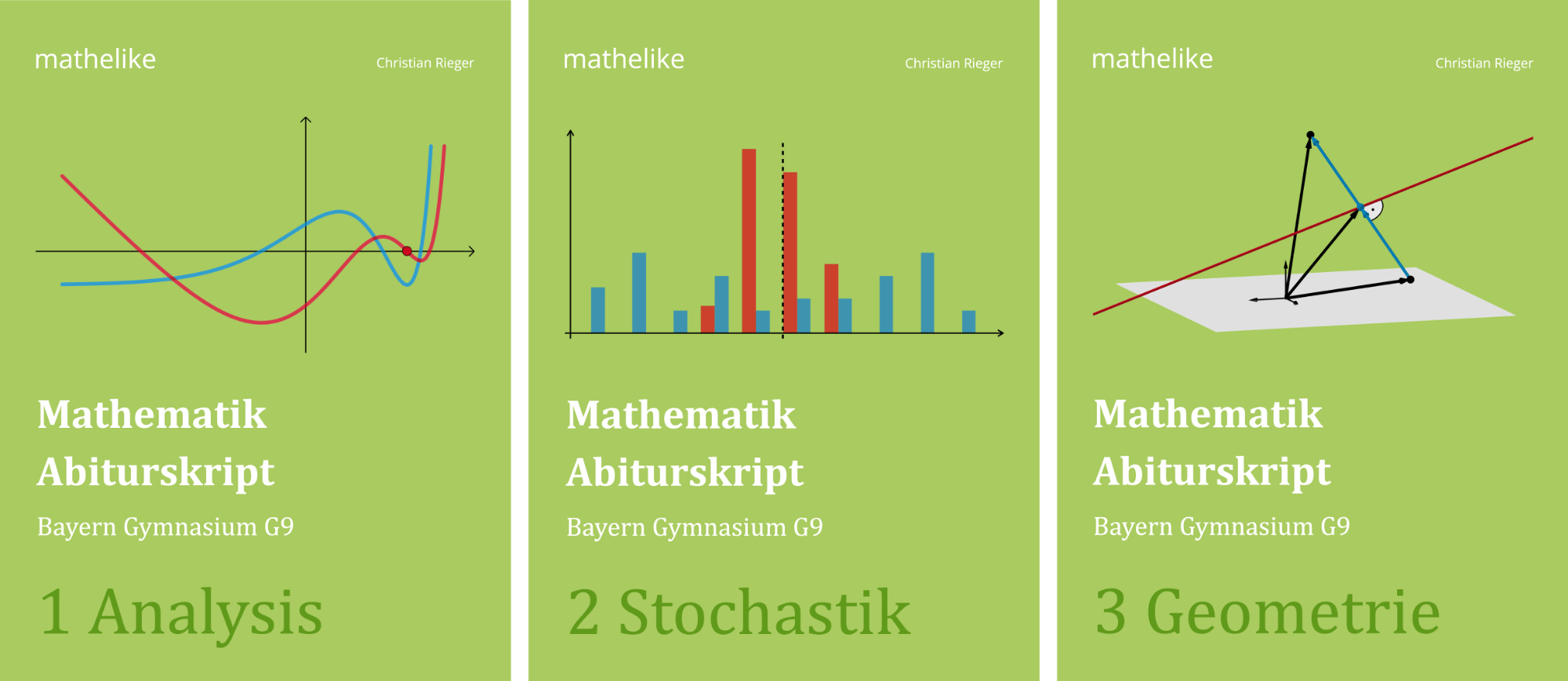

Beispielsweise liefert das Vektorprodukt \(\textcolor{#cc071e}{\overrightarrow{FA}} \times \textcolor{#cc071e}{\overrightarrow{FB}}\) der beiden linear unabhängigen Verbindungsvektoren \(\textcolor{#cc071e}{\overrightarrow{FA}}\) und \(\textcolor{#cc071e}{\overrightarrow{FB}}\) einen Normalenvektor \(\overrightarrow{n}\) der Ebene \(W\). Als Aufpunkt wählt man einen der Punkte \(A\), \(B\) oder \(F\). Damit lässt sich eine Gleichung der Ebene \(W\) in Normalenform angeben.

Lineare (Un-)Abhängigkeit von zwei Vektoren

Zwei Vektoren \(\overrightarrow{a}\) und \(\overrightarrow{b}\) sind

linear abhängig, wenn

\(\overrightarrow{a} \parallel \overrightarrow{b}\) bzw. \(\overrightarrow{a} = k \cdot \overrightarrow{b}\) mit \(k \in \mathbb R\) gilt.

linear unabhängig, wenn

\(\overrightarrow{a} \nparallel \overrightarrow{b}\) bzw. \(\overrightarrow{a} \neq k \cdot \overrightarrow{b}\) mit \(k \in \mathbb R\) gilt.

Lineare (Un-)Abhängigkeit von drei Vektoren

Drei Vektoren \(\overrightarrow{a}\), \(\overrightarrow{b}\) und \(\overrightarrow{c}\) sind

linear abhängig, wenn

sie in einer Ebene liegen bzw. wenn beispielsweise

die lineare Vektorgleichung \(\overrightarrow{c} = r \cdot \overrightarrow{a} + s \cdot \overrightarrow{b}\) eine eindeutige Lösung hat.

linear unabhängig, wenn

sie den Raum \(\mathbb R^{3}\) aufspannen bzw. wenn beispielsweise

die lineare Vektorgleichung \(\overrightarrow{c} = r \cdot \overrightarrow{a} + s \cdot \overrightarrow{b}\) keine Lösung hat.

Der Ansatz kann mithilfe der Normalenform in Vektordarstellung oder in Koordinatendarstellung erfolgen. Die Aufgabenstellung nennt zur Kontrolle eine Gleichung der Ebene \(W\) in Normalenform in Koordinatendarstellung (Koordinatenform).

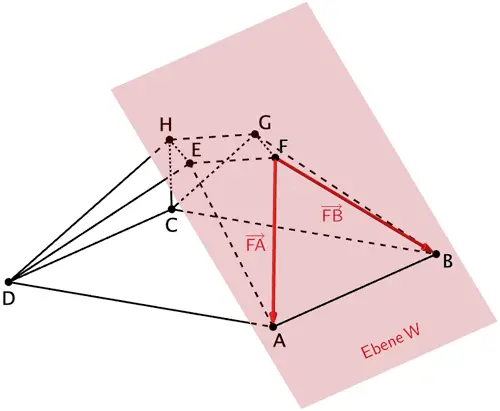

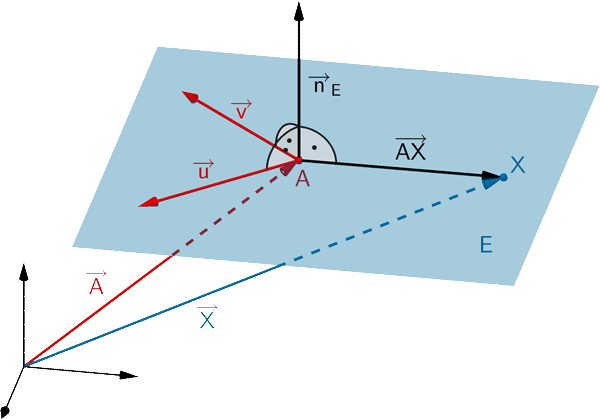

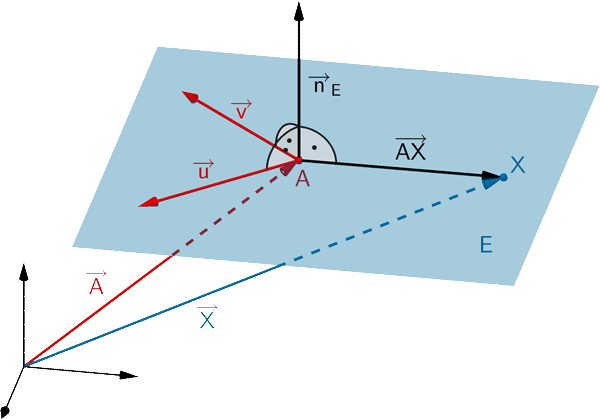

Ebenengleichung in Normalenform (vgl. Merkhilfe)

Jede Ebene lässt sich durch eine Gleichung in Normalenform beschreiben. Ist \(A\) ein beliebiger Aufpunkt der Ebene \(E\) und \(\overrightarrow{n}_{E}\) ein Normalenvektor von \(E\), so erfüllt jeder Punkt \(X\) der Ebene \(E\) folgende Gleichungen:

Normalenform in Vektordarstellung

\[E \colon \overrightarrow{n}_{E} \circ (\overrightarrow{X} - \overrightarrow{A}) = 0\]

Normalenform in Koordinatendarstellung

\[E \colon n_{1}x_{1} + n_{2}x_{2} + n_{3}x_{3} + n_{0} = 0\]

mit \(n_{0} = -(\overrightarrow{n}_{E} \circ \overrightarrow{A}) = - \: n_{1}a_{1} - n_{2}a_{2} - n_{3}a_{3}\)

\(n_{1}\), \(n_{2}\) und \(n_{3}\): Koordinaten eines Normalenvektors \(\overrightarrow{n}_{E}\)

Die Verbindungsvektoren \(\textcolor{#cc071e}{\overrightarrow{FA}}\) und \(\textcolor{#cc071e}{\overrightarrow{FB}}\) sollten aus Teilaufgabe a bekannt sein. Andernfalls werden sie wie folgt bestimmt:

\(A(5|5|0)\), \(B(-5|5|0)\), \(F(0|2|4)\)

\[\textcolor{#cc071e}{\overrightarrow{FA}} = \overrightarrow{A} - \overrightarrow{F} = \begin{pmatrix} 5 \\ 5 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} - \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 2 \\ 4 \end{pmatrix} = \textcolor{#cc071e}{\begin{pmatrix} 5 \\ 3 \\ -4 \end{pmatrix}}\]

\[\textcolor{#cc071e}{\overrightarrow{FB}} = \overrightarrow{B} - \overrightarrow{F} = \begin{pmatrix} -5 \\ 5 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} - \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 2 \\ 4 \end{pmatrix} = \textcolor{#cc071e}{\begin{pmatrix} -5 \\ 3 \\ -4 \end{pmatrix}}\]

Normalenvektor \(\overrightarrow{n}\) der Ebene \(W\) ermitteln:

Vektorprodukt (Kreuzprodukt)

Das Vektorprodukt \(\overrightarrow{a} \times \overrightarrow{b}\) zweier Vektoren \(\overrightarrow{a}\) und \(\overrightarrow{b}\) erzeugt einen neuen Vektor \(\overrightarrow{c} = \overrightarrow{a} \times \overrightarrow{b}\) mit den Eigenschaften:

\(\overrightarrow{c}\) ist sowohl zu \(\overrightarrow{a}\) als auch zu \(\overrightarrow{b}\) senkrecht.

\[\overrightarrow{c} = \overrightarrow{a} \times \overrightarrow{b} \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \overrightarrow{c} \perp \overrightarrow{a}, \enspace \overrightarrow{c} \perp \overrightarrow{b}\]

Der Betrag des Vektorprodukts zweier Vektoren \(\overrightarrow{a}\) und \(\overrightarrow{b}\) ist gleich dem Produkt aus den Beträgen der Vektoren \(\overrightarrow{a}\) und \(\overrightarrow{b}\) und dem Sinus des von ihnen eingeschlossenen Winkels \(\varphi\).

\[\vert \overrightarrow{a} \times \overrightarrow{b} \vert = \vert \overrightarrow{a} \vert \cdot \vert \overrightarrow{b} \vert \cdot \sin{\varphi} \quad (0^{\circ} \leq \varphi \leq 180^{\circ})\]

Die Vektoren \(\overrightarrow{a}\), \(\overrightarrow{b}\) und \(\overrightarrow{c}\) bilden in dieser Reihenfolge ein Rechtssystem. Rechtehandregel: Weist \(\overrightarrow{a}\) in Richtung des Daumens und \(\overrightarrow{b}\) in Richtung des Zeigefingers, dann weist \(\overrightarrow{c} = \overrightarrow{a} \times \overrightarrow{b}\) in Richtung des Mittelfingers.

Berechnung eines Vektorprodukts im \(\boldsymbol{\mathbb R^{3}}\) (vgl. Merkhilfe)

\[\overrightarrow{a} \times \overrightarrow{b} = \begin {pmatrix} a_1 \\ a_2 \\ a_3 \end {pmatrix} \times \begin {pmatrix} b_1 \\ b_2 \\ b_3 \end {pmatrix} = \begin {pmatrix} a_2 \cdot b_3 - a_3 \cdot b_2 \\ a_3 \cdot b_1 - a_1 \cdot b_3 \\ a_1 \cdot b_2 - a_2 \cdot b_1 \end {pmatrix}\]

\[\begin{align*} \textcolor{#cc071e}{\overrightarrow{FA}} \times \textcolor{#cc071e}{\overrightarrow{FB}} &= \textcolor{#cc071e}{\begin{pmatrix} 5 \\ 3 \\ -4 \end{pmatrix}} \times \textcolor{#cc071e}{\begin{pmatrix} -5 \\ 3 \\ -4 \end{pmatrix}} \\[0.8em] &= \begin{pmatrix} 3 & \cdot & (-4) & - & (-4) & \cdot & 3 \\ (-4) & \cdot & (-5) & - & 5 & \cdot & (-4) \\ 5 & \cdot & 3 & - & 3 & \cdot & (-5) \end{pmatrix} \\[0.8em] &= \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 40 \\ 30 \end{pmatrix} = 10 \cdot \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 4 \\ 3 \end{pmatrix} \end{align*}\]

Der Vektor \(\textcolor{#0087c1}{\overrightarrow{n} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 4 \\ 3 \end{pmatrix}}\) ist also ein Normalenvektor der Ebene \(W\).

Gleichung der Ebene \(W\) in Normalenform beschreiben:

Der Punkt \(\textcolor{#cc071e}{A(5|5|0)}\) dient beispielsweise als Aufpunkt.

1. Möglichkeit: Ansatz mit der Normalenform in Vektordarstellung

Ebenengleichung in Normalenform (vgl. Merkhilfe)

Jede Ebene lässt sich durch eine Gleichung in Normalenform beschreiben. Ist \(A\) ein beliebiger Aufpunkt der Ebene \(E\) und \(\overrightarrow{n}_{E}\) ein Normalenvektor von \(E\), so erfüllt jeder Punkt \(X\) der Ebene \(E\) folgende Gleichungen:

Normalenform in Vektordarstellung

\[E \colon \overrightarrow{n}_{E} \circ (\overrightarrow{X} - \overrightarrow{A}) = 0\]

Normalenform in Koordinatendarstellung

\[E \colon n_{1}x_{1} + n_{2}x_{2} + n_{3}x_{3} + n_{0} = 0\]

mit \(n_{0} = -(\overrightarrow{n}_{E} \circ \overrightarrow{A}) = - \: n_{1}a_{1} - n_{2}a_{2} - n_{3}a_{3}\)

\(n_{1}\), \(n_{2}\) und \(n_{3}\): Koordinaten eines Normalenvektors \(\overrightarrow{n}_{E}\)

\[\begin{align*}W \colon &\,\textcolor{#0087c1}{\overrightarrow{n}} \circ (\overrightarrow{X} - \textcolor{#cc071e}{\overrightarrow{A})} = 0 \\[0.8em] W \colon &\textcolor{#0087c1}{\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 4 \\ 3 \end{pmatrix}} \circ \left[ \overrightarrow{X} - \textcolor{#cc071e}{\begin{pmatrix} 5 \\ 5 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}} \right] = 0 \\[0.8em] &\,\textcolor{#0087c1}{0} \cdot (x_{1} - \textcolor{#cc071e}{5}) + \textcolor{#0087c1}{4} \cdot (x_{2} - \textcolor{#cc071e}{5}) + \textcolor{#0087c1}{3} \cdot (x_{3} - \textcolor{#cc071e}{0}) = 0 \\[0.8em] W \colon\, &4x_{2} + 3x_{3} - 20 = 0 \end{align*}\]

2. Möglichkeit: Ansatz mit der Normalenform in Koordinatendarstellung

Ebenengleichung in Normalenform (vgl. Merkhilfe)

Jede Ebene lässt sich durch eine Gleichung in Normalenform beschreiben. Ist \(A\) ein beliebiger Aufpunkt der Ebene \(E\) und \(\overrightarrow{n}_{E}\) ein Normalenvektor von \(E\), so erfüllt jeder Punkt \(X\) der Ebene \(E\) folgende Gleichungen:

Normalenform in Vektordarstellung

\[E \colon \overrightarrow{n}_{E} \circ (\overrightarrow{X} - \overrightarrow{A}) = 0\]

Normalenform in Koordinatendarstellung

\[E \colon n_{1}x_{1} + n_{2}x_{2} + n_{3}x_{3} + n_{0} = 0\]

mit \(n_{0} = -(\overrightarrow{n}_{E} \circ \overrightarrow{A}) = - \: n_{1}a_{1} - n_{2}a_{2} - n_{3}a_{3}\)

\(n_{1}\), \(n_{2}\) und \(n_{3}\): Koordinaten eines Normalenvektors \(\overrightarrow{n}_{E}\)

\(\textcolor{#0087c1}{\overrightarrow{n} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 4 \\ 3 \end{pmatrix}}\), \(\textcolor{#cc071e}{A(5|5|0)}\)

\[\begin{align*} &W \colon n_{1}x_{1} + n_{2}x_{2} + n_{3}x_{3} + n_{0} = 0 \\[0.8em] &W \colon \textcolor{#0087c1}{0} \cdot x_{1} + \textcolor{#0087c1}{4} \cdot x_{2} + \textcolor{#0087c1}{3} \cdot x_{3} + n_{0} = 0 \\[0.8em] &W \colon 4x_{2} + 3x_{3} + n_{0} = 0 \end{align*}\]

\[\begin{align*} \textcolor{#cc071e}{A} \in W \colon 4 \cdot \textcolor{#cc071e}{5} + 3 \cdot \textcolor{#cc071e}{0} + n_{0} &= 0 \\[0.8em] 20 + n_{0} &= 0 &&| - 20 \\[0.8em] n_{0} &= -20 \end{align*}\]

\[\Rightarrow \enspace W \colon 4x_{2} + 3x_{3} - 20 = 0\]

Beschreibung der besonderen Lage von \(W\) im Koordinatensystem

Da die \(x_{1}\)-Koordinate des Normalenvektors \(\textcolor{#0087c1}{\overrightarrow{n} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 4 \\ 3 \end{pmatrix}}\) gleich null ist, liegt die Ebene \(W\) parallel zur \(x_{1}\)-Achse.

Ebene \(W\) parallel zur \(x_{1}\)-Achse